“Est Libertatem Cogitatio”

“Libertas De Mentem”

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE QUAKER CITY SOCIETY OF FREE THINKERS

The American Revolution was a moment of great potential. Having thrown off the fetters of the crown and the church, many expected human-kind to achieve new heights. But among these opportunities lurked dangers. What would happen if the American people forgot the sacrifices that had been made along the road to freedom?

In addition to looking forward, the young country had to look back and pay homage to a line of free- thinkers stretching back through the millennia to ancient Greece. And so a few of Quaker Philadelphia’s more enlightened leaders, having a foot in the Old World, pledged to preserve this tradition of free thought by founding a secret society.

THE EARLY YEARS: KINDLING THE SPARK

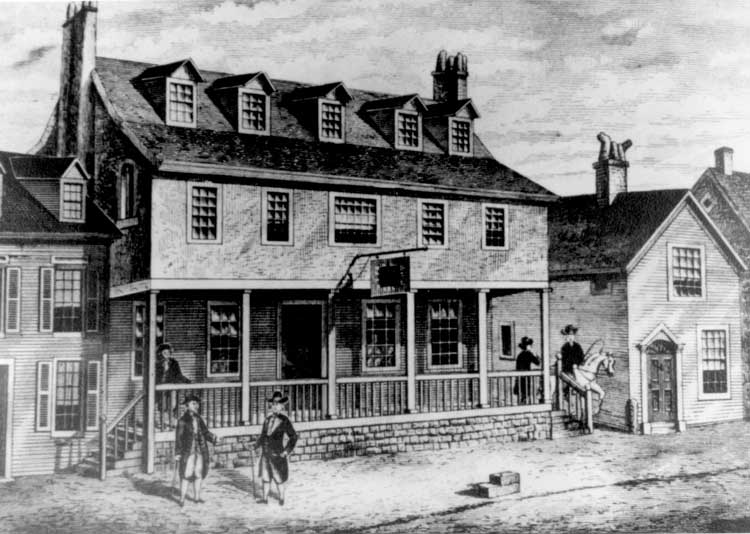

In 1732, a small circle of distinguished Philadelphia merchants and scientists formed the Quaker Society of Free Thinkers. Its purpose was to remember those who had dedicated their lives to the destruction of useless orthodoxies, and to continue the tradition of advanc-ing human progress by means of benevolent conspiracy. The charter members of the QSFT drew on both the membership and traditions of Benjamin Franklin’s trade-oriented Junto and the esoteric rituals of American Freemasonry. Meetings were generally held immediately after the closing of the Tun Tavern’s St. John Lodge No. 1, which allowed QSFT members to drain the kegs left behind by their masonic brethren.

Among the Society’s early members were Franklin himself, the astronomer David Ritten-house, noted botanist John Bartam, and Johannes Kelpius, who carried on his famous father’s experiments in caves near the Wissahickon Creek. They adopted as their mascot Giordano Bruno, the monk-philosopher who was burned at the stake for refusing to compromise the guidance of his divine reason in the face of earthly authority. Where the masons took as their symbols the surveyor’s tools of the compass, the ruler, and the plumb-line, the Free Thinkers adopted something even more primordial, two Simple Machines. The pulley symbolized upliftment while the screw embodied attachment to the universal core or essence, what Bruno called “the monad.” During the first meetings in the basement of Tun Tavern it was agreed that the group would keep no written records, with history and rituals transmitted to new initiates solely through the spoken word. Thus, very little can be firmly established about the history of the Free Thinkers, and what little we do know must be pieced together from fragments of evidence. These lie scattered, like hunks of obsidian, along the dark but lustrous trail that the Society’s membership has blazed through history.

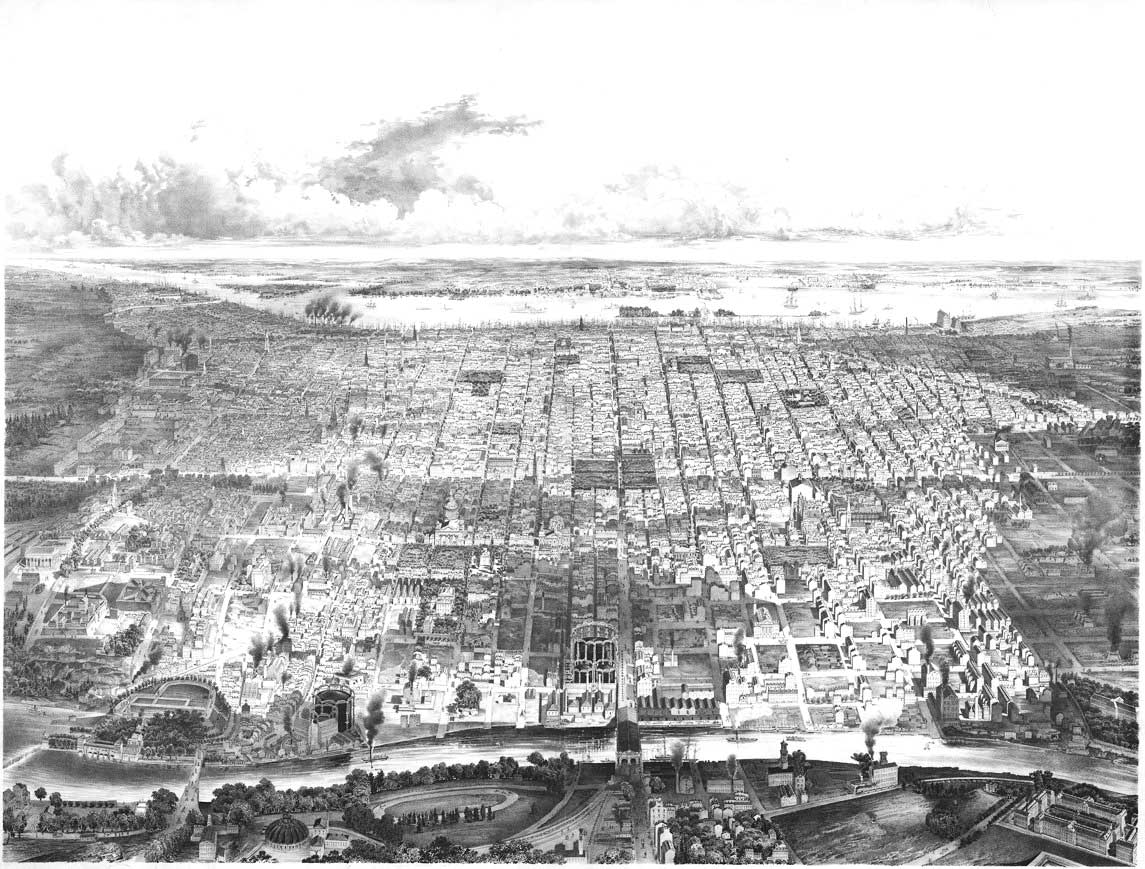

BIRD’S EYE VIEW OF PHILADELPHILA - 1857

LIGHTING THE WAY TO INDUSTRY AND VICTORY

Close analysis of the personal writings of members demonstrates the role the Quaker Society of Free Thinkers played in advancing the cause of Enlightenment during the early years of the Republic. Franklin himself had originally planned to fly an oaken key in his famous kite-and-key experiment until a fellow Free Thinker informed him of unsuccessful attempts to construct an electrical battery made of wood. During the 19th century, Free Thinkers Edgar Allen Poe and George Lippard drew from the Society’s deep well of esotericism to fuel their own work in the obscure and the occult. The Society’s spirit of open criticism and collaboration (albeit in a closed, hermetic environment) made Free Thinker membership an attractive proposition to the city’s artisans. The diaries of Frank Furness show that many of the most famous buildings constructed by the architect contain coded mathematical jokes intelligible only to his fellow Free Thinkers. A century before the Manhattan Project, a crack team of Free Thinkers perfected the ballistics and sighting of the Pennsylvania Rifle, which contributed to the Union’s victory in the Civil War.

ENIAC, the first military-grade supercomputer built at the University of Pennsylvania, was said to be extremely buggy until President Truman, who learned of the Society through Allen Dulles’s Skull and Bones connections, asked a hooded deputation of Free Thinkers to summon Franklin’s spirit in a midnight séance. The Society continues to share its facility with the spiritual lives of machines through partnerships with Bell Labs and some of Silicon Valley’s most prominent companies, and Society membership has influences the careers of numerous Philadelphia creators, from antiquity to the present day. Architects Edmund Bacon and Louis Kahn as well as graffiti pioneer Cornbread all drew support in their early careers from the Society’s Kelpius-Furness Initiative, which seeks to further the invention of novel street-level forms.

The artist Winslow Homer made his famous landscape paintings in his studio, but was only able to achieve the concentration necessary to envision these landscapes by locking himself into the Society’s windowless meeting room. The mysterious Toynbee tiles, laid into urban asphalt throughout the Western Hemisphere by Society member Severino Verna, are actually coded epigrams inspired by Society lore. Steven Grasse, a Society member descended from a long line of Pennsylvania printers, is believed to have used astronomical observations compiled by Franklin and David Rittenhouse to develop a method for predicting the weather based on the vascular patterns embedded in tobacco leaves.

In all cases, the respective artists works contain Society messages legible only to initiates. Wherever the arcane, the esoteric, the fantastic, and the strange have left their stamp on American arts and science, squint hard enough and you will see the Society’s mark.

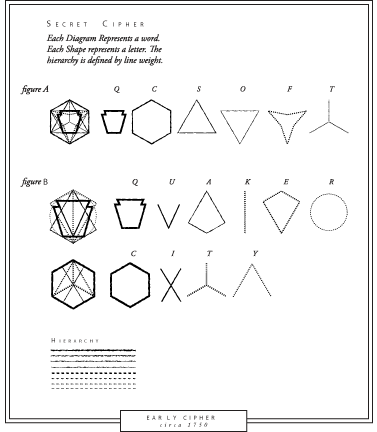

THE METHODS OF SECRECY

Despite Franklin’s admonition that “two can keep a secret, if one of them is dead,” the Free Thinkers maintained a tradition of strict secrecy through the Society’s first three hundred years. QSFT secretaries developed minimalist methods of record keeping. The few things that were written down, such as membership lists, passwords, and handshakes, were encoded in ciphers. Some of these codes, handed down from Franklin’s time, and eventually adopted by our country’s military and intelligence agencies. This penchant for secrecy had a dual purpose. For many years, certain areas of the Society’s expertise—particularly its knowledge of electromagnetism, lasers, nuclear energy, fluid dynamics, and jet propulsion—were thought to be dangerous if they fell into the wrong hands. (Most all of it gradually leaked into the minds of non-Society scientists, and from there, to Wikipedia.) Second, QSFT sought to preserve the highly closed and ritualized social conditions under which the first seeds of Enlightenment took root. In order to understand persecuted figures like Bruno, members had to experience knowledge as something precious.

Little can be said for certain about the QSFT’s present constitution and activities. Like most covert organizations, the Society’s doings only become visible with a few decades of hindsight. What can be said with some certainty is that the Society is active. It holds regular meetings and recruits new members from the rising generations. It continues to develop its elaborate symbology and scientific methods to keep pace with developments in technology and culture. In all likelihood, its full history will never be known and its very existence will remain a matter of dispute. This is just as the charter members of 1732 would have wanted it.